Every year, millions of people in the United States develop vertigo, a sensation that you or your surroundings are spinning.The sensation can be very disturbing and may increase the risk of falling. If you've been diagnosed with benign paroxysmal positional vertigo (BPPV), you're not alone—at least 9 out of every 100 older adults are affected, making it one of the most common types of episodic vertigo. The good news is that BPPV is treatable. Your physical therapist will use unique tests to confirm vertigo, and use special exercises and maneuvers to help.

What Is BPPV?

Benign paroxysmal positional vertigo is a common inner-ear problem affecting the vestibular system, a system used to maintain balance. BPPV causes short periods of dizziness when your head is moved in certain positions, relative to gravity. Benign means that this disorder is not life threatening, and generally, the disorder is not progressive. Paroxysmal means that the vertigo (spinning sensation) occurs suddenly. Positional means that the vertigo is triggered by changes in head position, most commonly when lying down, turning over in bed, or looking up. This dizzy or spinning sensation is called vertigo.

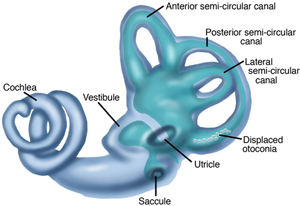

A layer of calcium carbonate material is present naturally in 1 part of your inner ear (the utricle). BPPV occurs when pieces of this material break off and move to another part of the inner ear, the semicircular canals (usually the posterior canal). These tiny calcium crystals (otoconia) are sometimes called “ear rocks.”

When you move your head a certain way, the crystals move inside the canal and stimulate the nerve endings, causing you to become dizzy. The cause of BPPV is usually not known; however, the crystals may become loose due to trauma to the head, infection, conditions, such as Meniere’s disease, or aging. BPPV is more common among females, and it may be hereditary.

How Does it Feel?

BPPV occurs most commonly following position changing, such as lying down, turning over in bed, bending over, and looking up. A short delay, often less than 15 seconds, may follow a position change before symptoms start. This dizzy sensation, called vertigo, is brief and intense and usually lasts for about 15-45 seconds. However, symptoms may last for up to 2 minutes if the crystals become stuck to part of the inner ear. The episodes of vertigo occur frequently for weeks or months at a time. During these episodes, you may feel like the room is spinning around you, and you also may feel lightheaded, off balance, and nauseous.

Signs and Symptoms

The signs and symptoms of BPPV usually last less than a minute. The signs and symptoms may come and go or may disappear for a period of time, and then recur. Movement of the head causes most of the signs and symptoms of BPPV, which may include:

Dizziness

A sense that you or your surroundings are spinning or moving (vertigo)

A loss of balance or unsteadiness

Nausea

Vomiting

How Is It Diagnosed?

The diagnosis of BPPV is based on whether you have a particular kind of involuntary eye movement (called "nystagmus"), and whether you have vertigo when your head is moved into certain positions. Your physical therapist will perform tests that move your head in specific ways to see whether vertigo and involuntary eye movement results. These tests will help the therapist determine the cause and type of your dizziness, and whether you should be referred to a physician for any additional testing.

The positional tests are meant to recreate BPPV symptoms. By moving your head into certain positions and watching your eyes, your physical therapist may determine the appropriate repositioning maneuver needed to reduce or eliminate your vertigo.

Many different types and causes of dizziness exist, and dizziness is difficult for people to describe, making BPPV and other causes of dizziness more challenging to diagnose. When talking to your clinician, be as specific as possible when describing your symptoms.

For example, explain if you have lightheadedness or if you see or feel the room spinning during an episode. Also, describe how long your symptoms last (seconds, minutes, hours, or days). Do your best to describe what makes your dizziness better or worse. For example, is your dizziness made worse by movement or position changes? Is your dizziness eased by stillness or rest?

Be sure to discuss any recent illnesses or injuries, problems with your immune system, changes in medications or hormones, or headaches. These clues will be very insightful for your physical therapist and can assist in establishing an accurate diagnosis, or indicate the need for a referral to another specialist.

How Can a Physical Therapist Help?

Fortunately, most people recover from BPPV with a simple but very specific head and neck maneuver performed by a physical therapist. Your physical therapist will guide you through a series of 2-4 position changes. Each position may be held for 30 seconds to 2 minutes, as prescribed by your physical therapist. These repositioning treatments are designed to move the crystals from the semicircular canal back into the appropriate area in the inner ear (the utricle). A repositioning treatment called the Epley maneuver is used for the resolution of posterior canal BPPV, the most commonly involved canal. No medication has been found to be effective with BPPV and, in some cases, medication could cause more harm.

In a very few cases, BPPV cannot be managed with treatment maneuvers, and a surgical procedure called a “posterior canal plugging” may be considered—but, surgical intervention is rare.

Can this Injury or Condition be Prevented?

No known ways exist to prevent BPPV, especially when caused by such factors as head injury or aging. Once a person has experienced BPPV, symptoms can return if new crystals break off and get into the semicircular canal, or if you dislodge loose crystals by placing your head in a certain position. Some people report that their BPPV symptoms recur predictably, perhaps seasonally, or with changes in the weather.

Within 3 years of having BPPV, about 50% of people may have a recurrence. BPPV resulting from head trauma is more likely to recur. Once a person has experienced BPPV, symptoms can return if new crystals break. Although your BPPV might return, you'll be able to recognize the symptoms and keep yourself safe until you can get help. Your physical therapist will apply the appropriate maneuver to return the crystals to their correct position in the inner ear, and also will teach you how to do exercises that can reduce or eliminate the symptoms.

Real Life Experiences

Laura B. is a 68-year-old woman with vertigo that began one morning 2 weeks ago when she got out of bed and the world started to spin. Since then, she's been having vertigo, nausea, and problems with her balance. When she visits her physical therapist, he gives her a special questionnaire to find out exactly what brings on her dizziness and balance difficulties. Turning over in bed, bending over, or looking up cause the most severe symptoms.

The physical therapist reviews Laura's medical history to make sure that no past condition may be contributing to the vertigo. He performs an examination, explains what tests he will use, and tells Laura that she should try to keep her eyes open and stay in position. The tests show that in certain positions, Laura's eyes move when they shouldn't, and she has vertigo that lasts 5 seconds. The therapist determines that she has the "canalithiasis form" of vertigo, which means that some crystals are displaced and are flowing through her semicircular ear canals, causing vertigo.

The therapist uses "canalith repositioning" to move the crystals into a proper position, using the Epley maneuver. Afterwards, he asks Laura to wait in the waiting room for a while so that he can retest her. Laura no longer has the symptoms that she had when the therapist tested her the first time, so he shows her how to do the canalith repositioning maneuver at home. She is to perform the maneuver once every day in the morning for 1 week, and then return to the clinic to make sure that she is progressing as expected.

This story was based on a real-life case. Your case may be different. Your physical therapist will tailor a treatment program to your specific case.

What Kind of Physical Therapist Do I Need?

All physical therapists are prepared through education and experience to treat people who have dizziness and balance problems. You may want to consider:

A physical therapist who is experienced in treating people with neurological problems.

A physical therapist with specialized training and experience in vestibular rehabilitation.

A physical therapist who is a board-certified neurological clinical specialist, called NCS, or who completed a residency or fellowship in neurologic physical therapy, or who has advanced knowledge, experience, and skills that may apply to your condition.

You can find physical therapists who have these and other credentials by using Find a PT, the online tool built by the American Physical Therapy Association to help you search for physical therapists with specific clinical expertise in your geographic area.

General tips when you're looking for a physical therapist (or any other health care provider):

Get recommendations from family and friends or from other health care providers.

When you contact a physical therapy clinic for an appointment, ask about the physical therapists' experience in helping people with inner ear injury.

During your first visit with the physical therapist, be prepared to describe your symptoms in as much detail as possible, and say what makes your symptoms worse.

Further Reading

The American Physical Therapy Association (APTA) believes that consumers should have access to information that could help them make health care decisions and also prepare them for their visit with their health care provider.

The following articles provide some of the best scientific evidence about treatment of BPPV. The articles report recent research and give an overview of the standards of practice for treatment both in the United States and internationally. The article titles are linked either to a PubMed abstract of the article or to free full text, so that you can read it or print out a copy to bring with you to your health care provider.

Hilton MP, Pinder DK. The Epley (canalith repositioning) manoeuvre for benign paroxysmal positional vertigo. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;12:CD003162. Article Summary on PubMed.

Helminski JO. Effectivess of the canalith repositioning procedure in the treatment of benign paroxysmal positional vertigo. Phys Ther. 2014:94(10):1373–1382. Article Summary on PubMed.

Helminski JO, Zee DS, Janssen I, Hain TC. Effectiveness of particle repositioning maneuvers in the treatment of benign paroxysmal positional vertigo: a systematic review. Phys Ther. 2010;90:663–678. Free Article

Cohen HS, Sangi-Haghpeykar H. Canalith repositioning variations for benign paroxysmal positional vertigo. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2010;143:405–412. Free Article.

Clinch CR, Kahill A, Klatt LA, Stewart D. Clinical inquiries: what is the best approach to benign paroxysmal positional vertigo in the elderly? J Fam Pract. 2010;59:295–297. Review. Article Summary on PubMed.

Fife TD, Iverson DJ, Lempert T, et al. Practice parameter: therapies for benign paroxysmal positional vertigo (an evidence-based review): report of the Quality Standards Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Neurology. 2008;70:2067-2074. Free Article.

Vestibular Disorders Association. Benign paroxysmal positional vertigo (BPPV). Accessed June 20, 2015.

Authored by Susan J. Herdman, PT, PhD; Shannon L.G. Hoffman, PT, DPT; Marcia Thompson, PT, DPT; Bob Wellmon, PT, PhD, NCS; and APTA’s Section on Neurology. Reviewed by the MoveForwardPT.com editorial board.